My introduction to The History Project came through my work with a different LGBTQ+ history project, the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project, as well as other research. Learning about the start of queer history in Boston, primarily the work of The Combahee River Collective, through research about the country’s lesbian feminist movement drew me into the work the project did and the work they are currently doing. Working out of Southwest Virginia on a very localized project, tracing the work of The History Project and historic social justice movements from Boston throughout the rest of the country allowed me to create personal and important connections.

The History Project began in 1980 when a $300 grant was awarded to a group of activists, historians, archivists, and writers to document the queer history of Boston. The project began as a slideshow of the city’s LGBTQ+ historic spaces, including bars and college campuses to show how queer people adapted to what Boston had to offer them. From there, the creation of public exhibits, such as Public Faces/Private Lives, began drawing more publicity and interest to the project. Since then, The History Project expanded from just physical exhibits and public events to the world of digital archives of digitized materials, crowdsourced digital archives, and the creation of off-shoot programs that began to focus on individual topics.

The History Project’s main objective as they document local LGBTQ+ history is to reclaim the stories and lives of those queer individuals who existed in spaces that may or may not have accepted them. Historically, LGBTQ+ individuals remained in the outskirts of society and in the shadows to avoid the faces of oppression and hatred. By bringing these stories and experiences within Boston back into the spotlight, The History Project aims to educate current and future generations about parts of their history they most likely never knew before.

Before diving into an analysis of all of the incredible projects and exhibits the project has worked on, past and present, it is important to recognize that they have set parameters for themselves for the community. These parameters focus on what The History Project does and does not want in terms of historic artifacts. While they are New England’s largest archives of LGBTQ+-related materials, like any group with a physical archive, there will be limited space. However, as the world moves ever so quickly into a completely digital age, The History Project has adapted and sports not only a physical archive but a digital one as well. As an organization, they will not purchase any materials from anyone but welcome both solicited and unsolicited – with the completion of a Donor Agreement Form – donations.

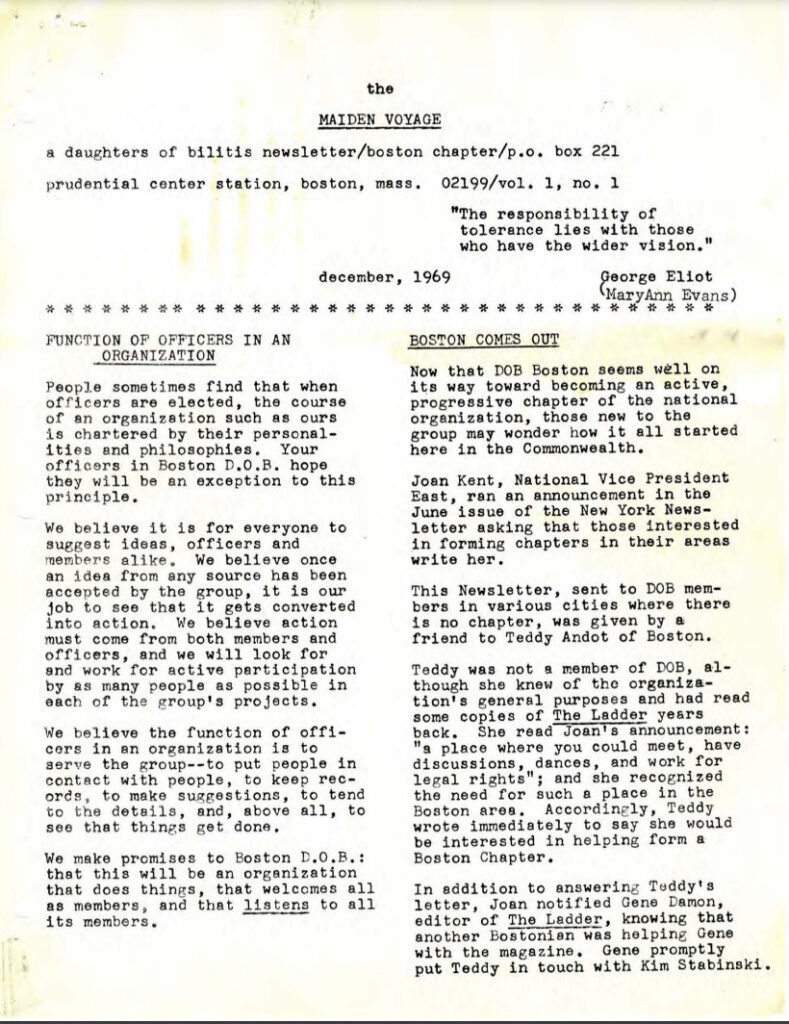

These donations become part of their physical archives and, if possible, scanned and uploaded into their digital archives. The archives contain materials ranging from scanned newsletters to buttons and t-shirts. For objects in their physical archive, The History Project volunteers created Finding Aids for each collection. Using these primary sources, The History Project crafted exhibitions, collections, and projects that develop and expand an intimate history of queer Boston. They have since digitized a few physical exhibitions that traveled throughout Massachusetts so that those in the current digital age may enjoy them, but there are still some that remain only in analog form. Their collections range from personal papers of individuals to images and organizations’ by-laws of activists and their work. Similarly, their projects look at celebrating the impact of historic occurrences, such as Gay Community News (GCN) a local Boston gay newsletter. The History Project has also created a crowdsourced project, #QueerArchivesAtHome, to not only engage the current LGBTQ+ community but to also shed light on small parts of LGBTQ+ history that may be otherwise forgotten.

These donations become part of their physical archives and, if possible, scanned and uploaded into their digital archives. The archives contain materials ranging from scanned newsletters to buttons and t-shirts. For objects in their physical archive, The History Project volunteers created Finding Aids for each collection. Using these primary sources, The History Project crafted exhibitions, collections, and projects that develop and expand an intimate history of queer Boston. They have since digitized a few physical exhibitions that traveled throughout Massachusetts so that those in the current digital age may enjoy them, but there are still some that remain only in analog form. Their collections range from personal papers of individuals to images and organizations’ by-laws of activists and their work. Similarly, their projects look at celebrating the impact of historic occurrences, such as Gay Community News (GCN) a local Boston gay newsletter. The History Project has also created a crowdsourced project, #QueerArchivesAtHome, to not only engage the current LGBTQ+ community but to also shed light on small parts of LGBTQ+ history that may be otherwise forgotten.

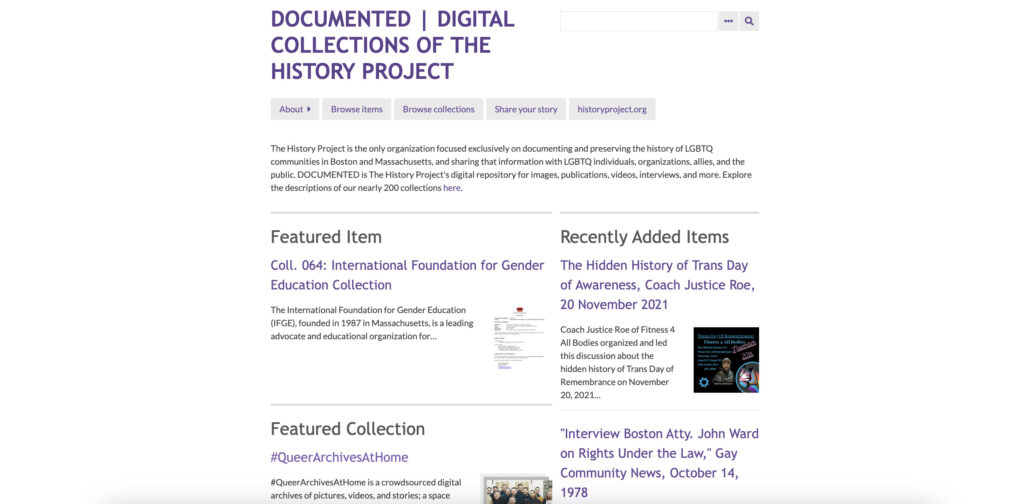

While The History Project has had decades to work through any problems they may have come across in creating their digital site, there are some drawbacks that raise questions of being user-friendly. The biggest setback that hinders potential research and easy access to the digital archives is the fact that in order to find the digital archives, one must carefully look for the link. This link can be found on the page that discusses The History Project’s collections in general but there is no direct way to access this archive from their main page. The link itself is also in a smaller font than all of the other words on the page and if you are not actively looking for the link, you may or may not notice it. The one upside to their collections page is that those collections that are available in digital form do indicate as much but again, it may not be as obvious to those outside the project.

Continuing this conversation about The History Project’s digital archives, once you find it and recognize that it is present on their page, it is an incredible resource. They have both historic and more recent artifacts, newsletters, pictures, etc. If someone was to use this archive to write a research paper or just learn more about Boston’s queer history, they would have more than enough sources and information to do so. Within the digital archives, there are clear headings indicating an item search or a collection search and even a way to contribute to the archives.

Overall, The History Project has become one of the country’s largest and most well-known LGBTQ+ history projects. This is not only because of the work they have completed in the past but also because of the work they are continuing to do. As the main mission of the project states, their goal is to preserve history and educate current generations of queer people about their past. Other than a few slight bumps in the road, I do believe The History Project has met this goal and is continuously exceeding it every day.