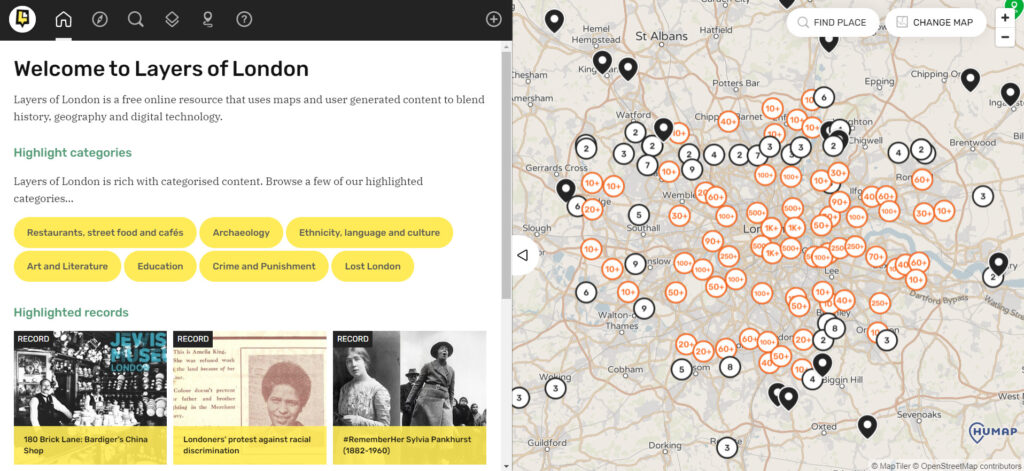

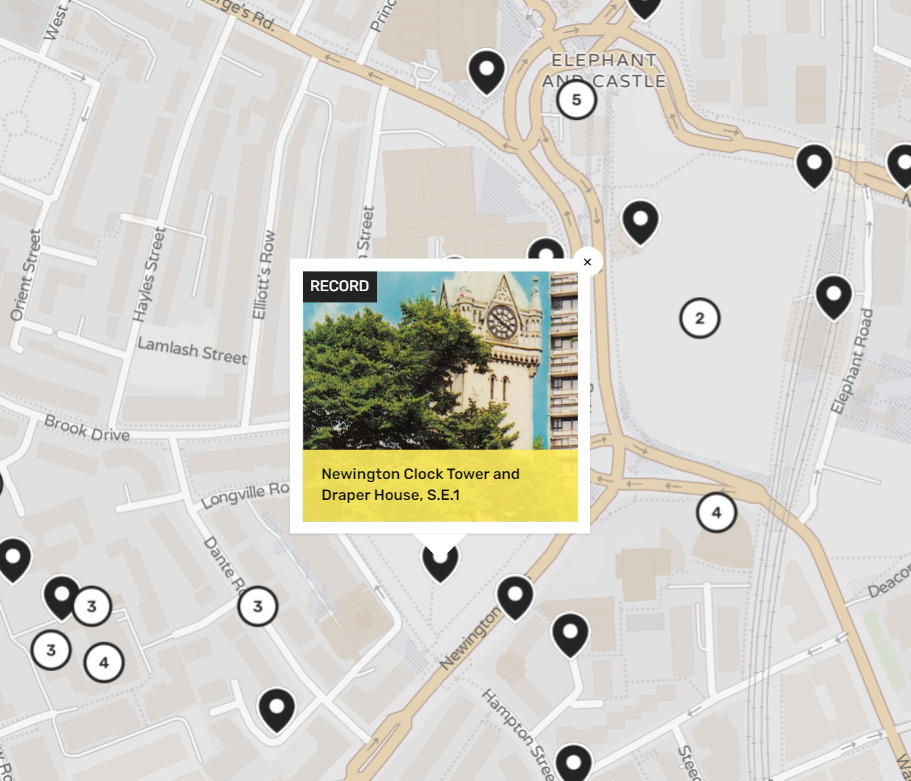

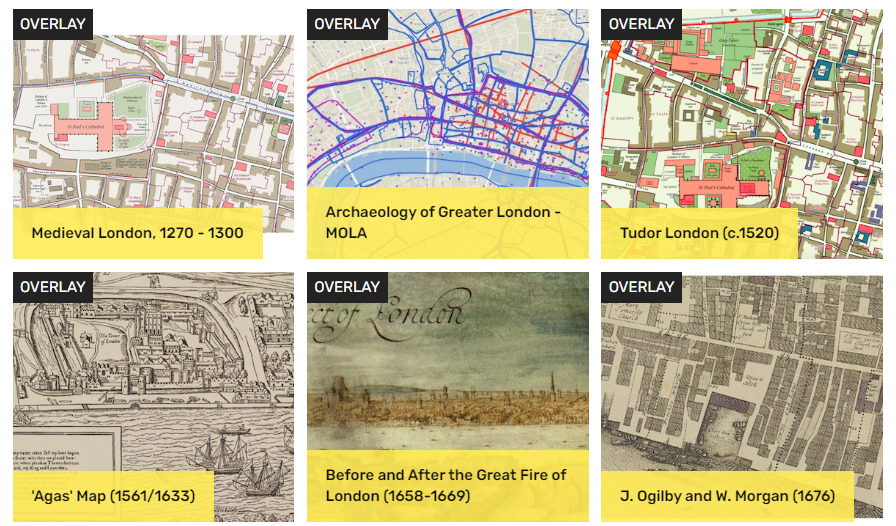

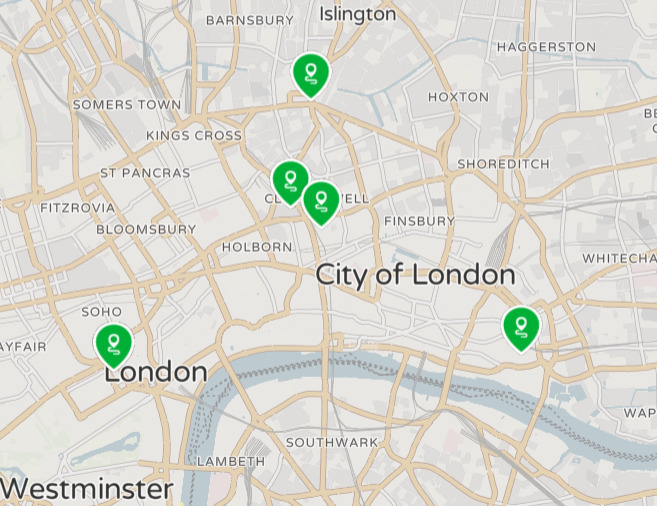

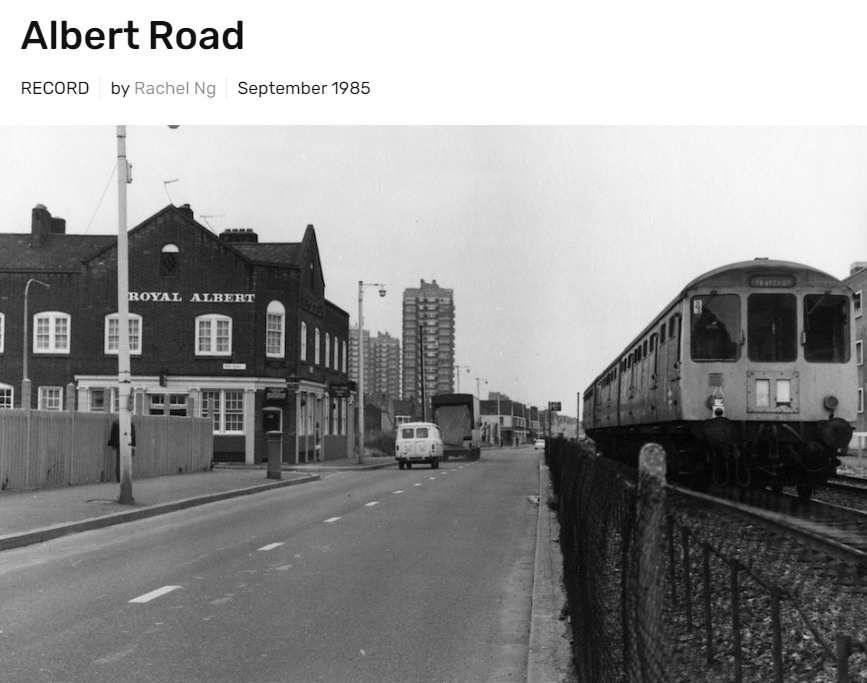

Layers of London is a digital history project that was developed by the University of London’s Institute of Historical Research. The project is a map-based one, utilizing geographic information systems to mark locations on a map. These locations can range from the personal stories of people from throughout London’s history to the locations of historic buildings, to the locations of movements. These markers also have a considerable range of time from which they can originate, the map having markers that date back a millennium. These markers are all placed over a current map of London, however, overlays of older maps can be used as well.

Layers of London was made in collaboration with several local archives, institutions, and communities as well as the British Library, The London Metropolitan Archives, Historic England, The National Archives, and MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology. Layers of London began development in 2016 and continued to develop through 2020. The project benefitted from funding and voluntary support through its developmental phases and its evaluation phases until its current stage, resulting in the project that is publicly accessible today. The project is still considered ongoing as institutions and the public has access to add their own markers and stories to the map. Layers of London was created with the idea in mind that communities in London would have the ability to create a social historical resource about their area. This meant that there would be, for the first time, a collection of digitized histories of London that includes everything from maps, photographs, recordings, and written stories of Londoners of all backgrounds throughout history.

The project is aimed, quite clearly, at creating a resource of digitized histories that have geo-specific locations, however, this map also serves as a mode for understanding how London has changed over time. With digitized resources from all over London and from any time in the last millennium, Layers of London can provide an in-depth look at how London has changed, not only physically, but economically, socially, and politically.

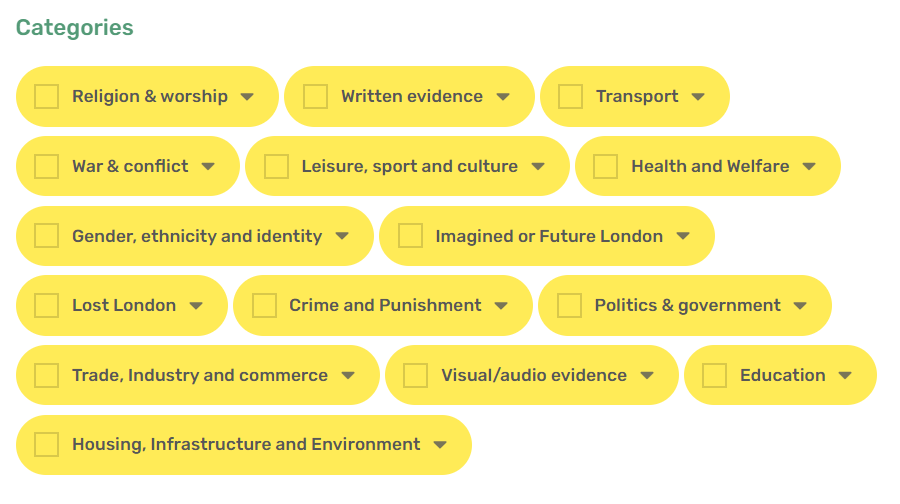

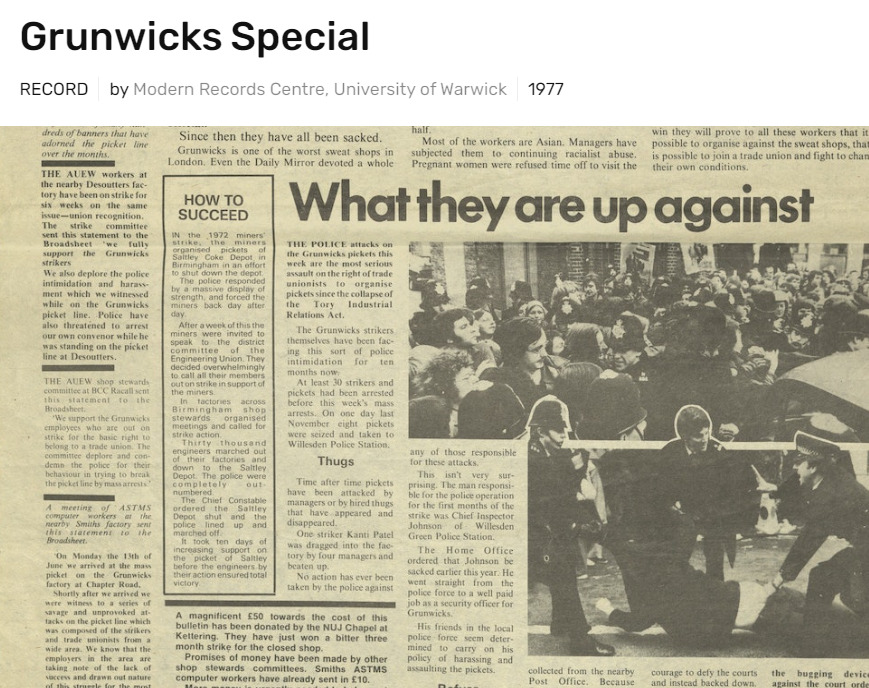

One of the benefits of how the project is set up is the way that it allows for filtering of the information that is available on the map. Because of this, the changes that London has experienced become easily accessible with filters such as religion and worship; war and conflict; gender, ethnicity, and identity; politics and government; and trade, commerce, industry, and commerce. So while the project may have begun as an effort to allow for institutions and local communities to contribute information about their social history into a single collection.

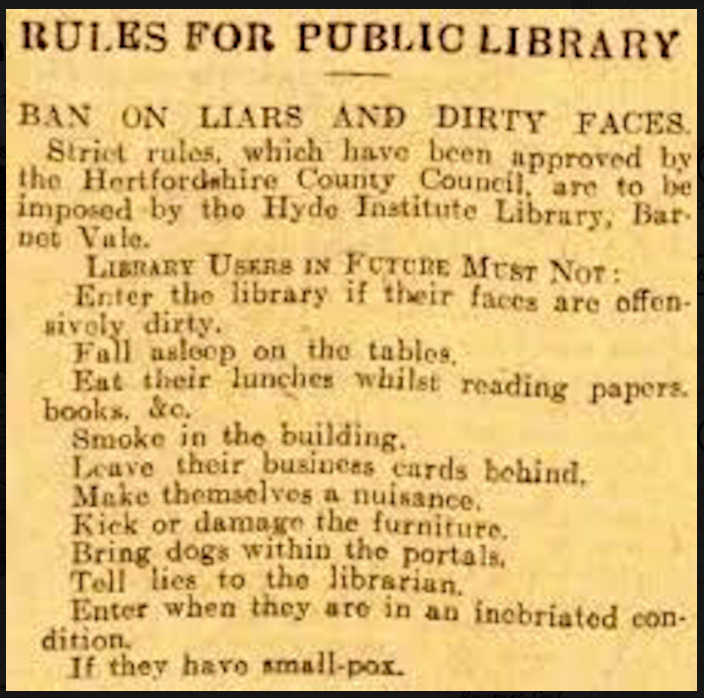

One thing this collection does really well is collecting information, which while that may seem to be a redundancy, the nearly 12,000 records that have been digitized and added to the project show how well the Layers of London map has done at becoming a source of information and history. As previously mentioned, these records span a broad range of locations, time periods, themes, and peoples. Its accessibility is also commendable as it is both open to the public for research and contribution purposes. Similarly, when it comes to ease of use, the website offers several guides on how to navigate the website and its collection. The amount of information available about London’s extensive history in this digital project surely makes it an excellent source for academic scholars and casual researchers alike.

One problem that comes with this project, however, is the fact that all the information can be overwhelming, and even with filtering, there is still an excess of information that appears for every topic. Part of this is because the records can have multiple filters—which while this can be a useful feature, can mean that a search may pull 800 records that are distantly related to the filtered topic. For example, a search on gender will pull personal records of people because they are listed as male or female, even if the record has no relation to gender history in London. So while the amount of information available on the website is beneficial, the project could still use some reconstruction of its search function.

Another criticism of the project relates to the information available on several minority groups, ethnic and religious alike. One example of this is regarding the presence of slaves in the available records. Only 55 records appear regarding enslaved people, and they are, for the majority, records of coffee houses where slave trade occurred. There are few personal stories or other personal records of anyone who lived as an enslaved person in London or their families. These records do not even include records of the enslaved people who passed through the coffee houses, merely just a mention of enslaved people being sold through the businesses. Similar things can be said about searching for other minority groups on the site, and while some of this may be caused by a lack of records available for these groups, it could also be caused by these same groups having less access to resources that would allow them to contribute their own histories.

Ultimately, Layers of London is a digital history project that has a wealth of records and resources for researchers, students, and the public, some of which may have only ever been shared among communities had this site not been developed. This project creates an accessible resource that not only provides numerous records that have geo-specific locations, but also provides an incredible look into the physical, economic, social, and political changes that London has experienced over the past millennium.